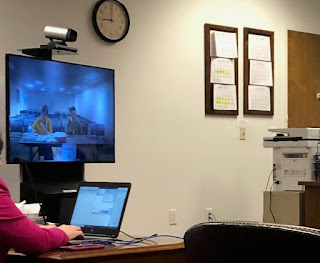

This morning, February 14, I attended the hearing for Mario and his two younger children at the Brownsville immigration court, essentially a large tent right next to the bridge to Matamoros in which rooms have been created with television screens. I knew that the judge and interpreter would not be physically present—they were at the immigration court in Harlingen, 25 miles away. A video camera would be on them so they would be broadcast on the screen.

Even though I agreed to be the sponsor for Mario and his kids if they were granted asylum, I was not allowed in to attend Mario’s hearing. The lawyer, Cathy Potter, who took this case on as “low bono” had thought they would let me in. Because they didn’t, she gave me her car keys and I hightailed it to the Harlingen courthouse. Two people from out of town wanting to witness a case in person had already been told that they were not allowed in. Because of my relationship with Mario and his wanting me to be there, I was allowed in.

I sat on the far side of the room so I could see Cathy and Mario on the television screen. There were at least 25 empty chairs behind them. I was the only person in the room who wasn’t the judge, the translator, or the lawyer representing the government. When the lawyer for the government spoke, the video camera was set on her, and I could be seen in the background. Mario waved at me. I was glad he knew that I was watching what was happening.

I was impressed by how Cathy asked Mario questions to get his story out. He is from a small town in Honduras but found a good job in the city of Pimiento. He worked at a clothing factory. He was appreciated and hardworking. A man that Mario knew from much earlier in life had joined the gang MS-13 and moved back to Pimiento. This man came to Mario’s house with two companions and requested that Mario sell drugs at his factory where over 2,000 people worked. Mario refused and his acquaintance said he had a week to think it over–and if he didn’t agree he and his children would pay the consequences.

It was a heartbreaking and terrifying story. Mario broke down in tears when asked about moving away from his extended family. The government’s attorney asked Mario several questions and then it was over. There was a recess at the end of which the Judge said she would give an oral decision. I drove back to Brownsville and waited outside the Brownsville court to learn the judge’s decision. As I waited, I met seven people from all over the country, people who had come to help and witness what is going on.

When Cathy finally exited, she told me that Mario’s request for asylum was denied. She said that the judge acknowledged that she believed Mario but the law requires a certain amount of evidence to grant asylum. Cathy told me from the very beginning that very, very few migrants meet this bar. The bar to demonstrate persecution is so very high—and very few people can meet this, even people who have been kidnapped and hurt. She also said that most go into these hearings without a lawyer, and no one who represents themselves has been known to win their case. This has been the experience of many of Mario’s neighbors. Some told me that they had a tremendous amount of evidence and that they were still denied—but they didn’t have a lawyer. The law requires a certain type of argument and demonstration of persecution—and this is why the presence of a lawyer makes it 17 times more likely of winning the case–and still the probability is very low.

Once Mario and his kids were back in Matamoros, all I could do was give them hugs, talk with them, tell them I’m sorry. I gave Mario some money and told him that I will stay in touch. I will reach out to the people I know in San Miguel, a city in a relatively safe part of Mexico. He needs to find a place to where he can move, find a job and live without worrying about his family’s safety. I’m deeply saddened that entering the United States is not an option for them. I’m angry at how the U.S. immigration law works.

Mario is a hardworking individual, communicates well, and demonstrates a deep commitment for his children. I believe he can find a new life in a new place, but it’s identifying where and taking the leap that he now needs to do. He wants to file an appeal so that he can stay in the camp, but that will most likely simply delay the inevitable.

Until the laws change, refugees with real reason to leave family and friends to seek a new life will be stymied at the U.S. border. Cities like Matamoros will have areas that are essentially concentration camps. Although the conditions are better than when I visited in October, the people living there are living in a dead end. I admire how they hold on to hope and how, at least in Mario’s neighborhood, the people are taking care of each other.

I encountered a staggering number of people from all over the United States wanting to be of help, both in meeting the basic needs of these people and in changing the laws to be more humane. I met people from many different organizations, including Angry Tias and Abuelas. I talked political strategy with a number—more pressure needs to be applied to our federal representatives to end the Migrant Protection Protocol. I take heart at the numbers of people so concerned about this issue that they are going down to the border themselves.

So I return with grave disappointment that Mario and his children cannot enter the United States while I take heart there are people with courage and resilience both within the camp and outside, committed to finding a more humane way forward.

Love with Courage,

Alan